Last week, we explored two major meanings of “materialism” that often get confused: ontological (or metaphysical) materialism, on the one hand, and methodological materialism, on the other. Today, we need to dig into a third use of the word: dialectical (and/or historical) materialism. So, what is that?

Now, this is a question that often makes writers rather too wordy, so I am aiming to offer a tight summary.1 That means I will leave a lot out, but I think my presentation will be accurate, even if not perfectly precise. I also want to be clear that my academic background is not in Marxist theory, in particular, or even political economy, in general.2 My engagement with Marx and Marxist and Marxian thought here will then be general and summary in form. I am sure that any more focused scholar of Marxism will have plenty of critiques of my outline below. Again: my goal here is accuracy, but not always precision. That said, of course, (polite!) critiques in the comments are always welcome.

The “dialectical” part of dialectical materialism is derived from the work of G.W.F. Hegel, whose (famously complex, opaque, and torturous) philosophy argued, in part, that history was the dialectical unfolding of a truth that is as of yet held only in potentiality rather than in actuality. What this means, for Hegel, is that history began with a set of primitive states of being, and that, over time, those states come into conflict (thesis and antithesis). Those conflicts do not result, though, in the victory of one over the other; instead, through the conflict, some new state is generated, that generally contains at least some of both of the previous two states (synthesis). So if, for example, there was some conflict between shamans and chiefs in our deep past, the resolution in history would not be the victory either of the religious leaders or the political leaders, but rather some new state of affairs that “sublated” both of them into a more complex and functional system: perhaps, for example, a new class of priest-kings who arrogated to themselves both spiritual and political leadership.3

For Hegel, over time, this constant process of dialectical conflict and its resolution, via sublation, into newer, more complex, and more philosophically astute or “true” modes of social organization, is the “purpose” of human life in history. In time, we will arrive at the true and best mode of existence, having arrived there only through the long and twisting dialectical channels of historical conflict and development.

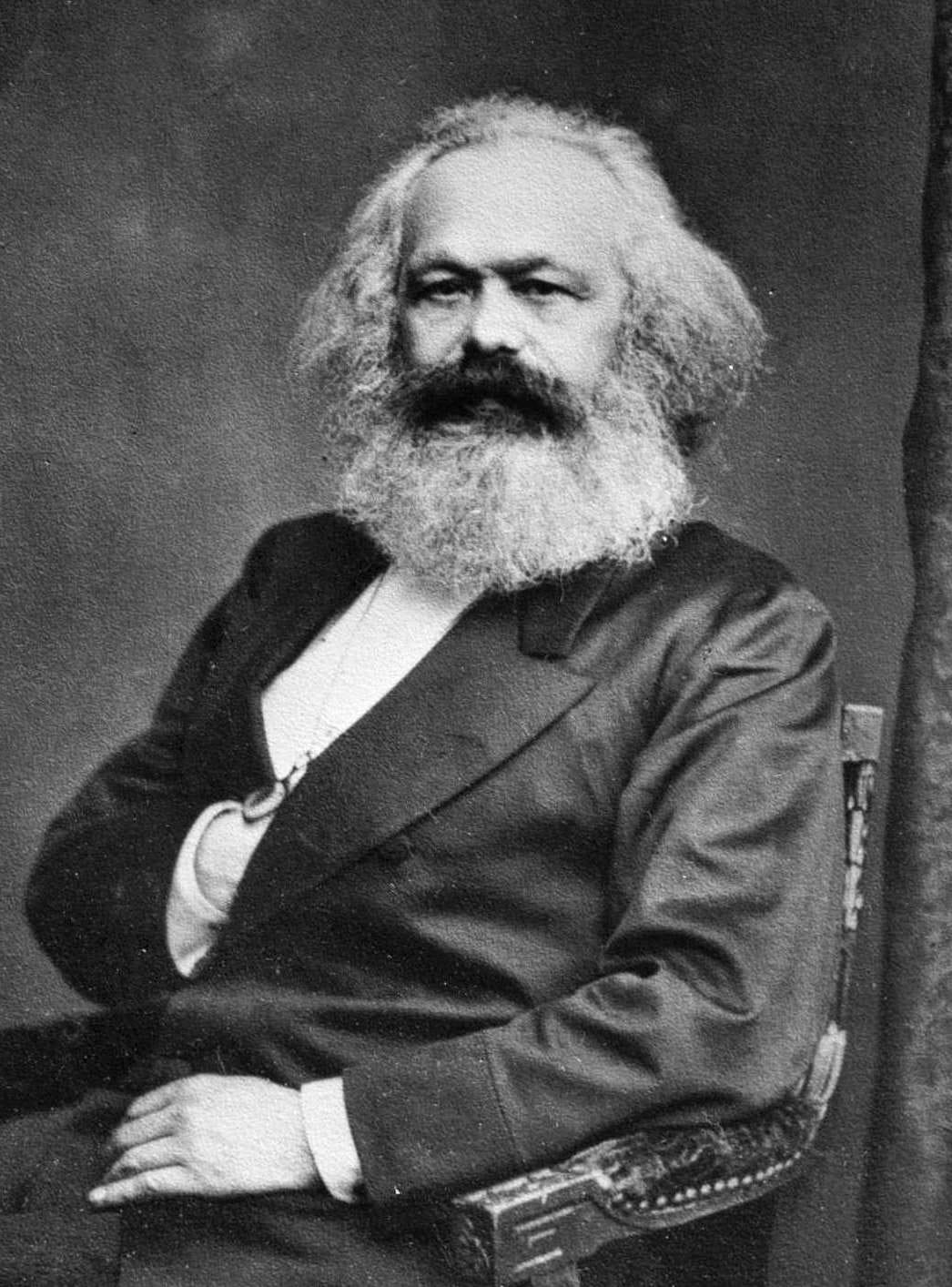

Now, Hegel’s thought has been appropriated, applied, and (frankly) twisted by all kinds of thinkers over the past 200 years. One major stream of his interpreters was the so-called “Left Hegelians”, who saw in his work a secular philosophy that could draw on what was best about Christian theology while leaving actual Christian belief and practice behind (the “Right Hegelians”, as you can imagine, saw things rather differently). Karl Marx lived a generation or so after Hegel, and was in the vague stream of Left Hegelianism: he agreed that history developed dialectically over time into newer—and indeed, better—forms of social, economic, and political organization.

However, he took major issue with one of (what he saw as the) major elements of Hegel’s system. Hegel is understood as an idealist, indeed, he is often described as an Absolute Idealist. Now, “idealism” is a term just as overdetermined, vague, and misused as “materialism”—indeed, maybe more so—but as I said above, I’m trying to not be overly wordy here (as surprising as that may seem to you, gentle reader, considering the volume of words I am currently exposing you to), so I will not attempt any serious exploration of idealism(s). In general, though, ontological or metaphysical idealism argues that reality is, at its core, basically “mind”-like, that what is real is phenomenality, qualia, the immediate presentations to mind. On this view, matter is either unreal, less-real, or simply derivatively real—depending on your flavor of idealism. (It is important to note that one could subscribe to methodological materialism while being a metaphysical idealist. But I am getting ahead of myself.) The important thing to note is that ontological or metaphysical idealism is the direct opposite of ontological or metaphysical materialism.

For Marx, Hegel’s idealism was a problem. But his understanding of idealism was different from what I just outlined above (and again, “idealism” means a variety of things, so this isn’t necessarily surprising). He understood Hegel as arguing that people’s ideas about the world came into conflict, and that those ideas are what drove history. So, for example, the shamans had some kind of spiritual idea of society, and the chiefs had some kind of political idea about society, and they fought over which idea would win out and be dominant (and, in the process, generated a new idea which was the synthesis of the best, or at least the most effective, aspects of each of the previous ones).

Marx thought this was an error. He noted that people’s ideas of what was right, just, and good strongly tended to be aligned with their material interests. So, for example, a priest thinks that people should go to (or, at least, tithe to) their local church. Aristocrats think that only aristocrats should make important decisions. Slaveholders think that slavery is just fine, etc. For Marx, it was a mistake to think that these people arrived at their ideas of what was good first, and then fought over those theories. Instead, their ideas developed precisely from whatever social, political, and economic forms would be best or most convenient for them, materially speaking (that is, made them wealthier, more powerful, or more prestigious, etc.). Obviously, if a priest has gone through all the trouble of getting ordained, it would be a real bummer for them if all the churches closed. Likewise, if an aristocrat admitted that often non-aristocrats have good ideas and are competent leaders, that might lead people to question whether there should be an aristocracy to begin with.4 And again, if a slaveholder admitted that maybe enslaving people wasn’t a very nice thing to do, they might have to free all those they enslaved. And that would be bad for their bottom line, because then who will do all the back-breaking labor that allows them to profit?

For Marx, then, political ideas were really just manifestations of material interests (or, put another way, our ideals always reduce to our material conditions), and so a competent theory of political economy had to be materialist in this historical and social sense: if we want to explain why, for example, feudalism arose in medieval Europe, we should look to demographics, agriculture, military technology, the weather, etc.—and not to what political ideas the philosophers were arguing about, since, as far as Marx was concerned, those ideas would be determined by the material interests of those philosophers (or whoever was paying them to write).

So, Marx proposed a dialectical materialism to replace Hegel’s dialectical idealism. And it has to be said that Marx’s proposal proved a very powerful tool in the study of history, economics, political science, and related fields.5 And this shouldn’t be surprising; indeed, I don’t think most people would find Marx’s basic point here all that controversial: of course people tend to believe that the social structures that benefit them are good. That’s hardly rocket science.

However, it’s important to note that Marx seems to have misunderstood Hegel, at least to some degree. This isn’t surprising, not only because Hegel is notorious for being hard to understand, but also because, in my opinion, Marx himself wasn’t really a philosopher per se.6 It’s really no mark against him that, despite being probably the most influential and insightful political economist of all time, whose thought continues to be productive nearly two centuries after he wrote, Marx nevertheless doesn’t have a strong grasp on topics like ontology or theology. No one is amazing at everything.

Even so, Marx’s errors in reading, interpreting, and applying Hegel matter, because they demonstrate two fundamental misunderstandings not only about Hegel, but about philosophy more generally.

First off, Hegel’s idealism, as already indicated above, was an ontological, and indeed metaphysical, commitment. He understood material realities as essentially reducing to “ideal” realities. But this does not mean that he thought that “ideas” were some kind of entity apart from matter that imposed themselves on the material world, offering some kind of non-materialist causality. Instead, Hegel was offering a monistic explanation in which “ideal” or “mental” events, on the one hand, and “material” events, on the other, are really just two sides of the same coin, even if he believed that the latter is reducible to the former in some way.

In other words, I don’t think Hegel would have been bothered at all by Marx’s argument that the material interests of a person shaped their political ideals. Marx seemed to have interpreted Hegel’s “idealism” as equivalent to the “Great Man” theory of history, by which historical turning points are caused by important, smart men in positions of power. Under such a view, the particular ideas that such a leader holds can have outsized influence on historical events, as they make sovereign decisions that might move their society away from the path it might have naturally followed. Under this view, things like democracy, capitalism, and socialism are basically ideas that some super smart guy cooked up in his library one day and then forced on society through force of will and political machination.

But this is, of course, has nothing to do with Hegel’s position at all. When Hegel famously said that Napoleon was “the World-Spirit on horseback”, he wasn’t arguing that Napoleon was able to assert his particular ideas on Europe, but just the opposite: that the ideas that were most powerful were essentially in control of Napoleon, and employing him for “their” ends (if I may be allowed a bit of anthropomorphizing). Napoleon was just the vessel of the current dialectical struggle, and that struggle could be summarized in the “big picture” of political theory, or in the granular analysis of material interests. My own view is that, for Hegel, these were just two sides of the same coin.

But for Marx—and certainly for many Marxist and Marxian thinkers today—they were instead two opposed viewpoints, and one of them was wrong. Marx (with his pal Engels) famously said that they found Hegel sitting on his head and that, with their improved understanding of the dialectical process of history (trading idealism for materialism) they sat him the right way round. But I think this conclusion was generated by a fundamental confusion about what idealism and materialism should mean in this context. As I have already said above, I don’t think that a historically-materialist explanation is really at odds with Hegel’s system at all. It’s another way of accounting for the dialectical unfolding of reality.

It seems that, whether he realized it or not, Marx was assuming a kind of dualist reading of Hegel, which is definitely a big no-no. Hegel was certainly offering a monistic philosophy, in which matter is understood as an expression of mind or spirit. When Marx talks about a materialist causation in human history, though, he’s not really making an ontological claim at all, but only a claim about which kinds of interests actually motivate people—that is to say, what kinds of thoughts, feelings, or interests are most prevalent in their decision-making.

This is an important clarification, because it drives home the fact that, even for Marx, dialectical or historical materialism is still fundamentally about human minds, human subjects, even if he wants to elide that, not only with his vague employment of the term materialism, but also with even vaguer references to, for example, the idea of classes of people operating as subjects (I think it’s hard to imagine a clumsier example of reification). Again, though, I don’t really mean this as criticism of Marx’s political economy, which I still find to be the most insightful and helpful theory around. It’s just that, when this political economy is inflated into a pseudo-ontological (or even crypto-metaphysical) system, it can’t bear the weight it would need to hold.

In other words, dialectical or historical materialism is truly a third meaning of materialism, which is quite distinct from either ontological/metaphysical materialism or methodological materialism. Importantly, it seems to me that a dialectical materialist could actually be an ontological/metaphysical idealist, or a dualist, or indeed an ontological/metaphysical materialist. There is no necessary connection between these different modes of materialism, though, because they are seeking to explain or describe different things, and they operate at different levels of analysis.

Certainly, and again, to be clear that this is no take-down of Marx: my own view is that Marx still offers basically the best political economy around.7 Although his view has been improved on by scholars who came later, and doubtlessly can still be improved still (and, of course, can be critiqued in many ways), his basic framework has extraordinary explanatory power. But this dialectical/historical “materialism” does not entail commitment to any other mode of materialism. That’s important for a number of reasons, but certainly it’s critical for any spiritual or religious person who wants to engage meaningfully with Marxist or Marxian thought. One can adopt a dialectical and historical materialist account of the development of human society and also believe that ontological or metaphysical materialism is false (of course, one can also affirm them both—my point is just that there is no necessary connection between them.)

I hope that the above discussion points clearly to the need to be specific and even technical when we use words like “materialism”, because that one word covers a number of quite distinct ideas within even quite different fields of study and discourse. When we confuse those different meanings, we render this word—and many words like it—rather vague and meaningless. In truth, we can’t even really disagree with others unless we have very clear definitions for terms like this. Indeed, it seems to me that not a small amount of internet bickering isn’t so much genuine disagreement about substantive issues but is rather two (or more) people using the same word, but assigning different meanings to it—often with none of the interlocutors realizing this. I hope that this post can both help clarify the term “materialism” and also encourage us all to make sure we know precisely what we—and our interlocutors—think we mean by a word when we use it, especially in philosophical discourse.

As the length of this post resolutely manifests, even a “tight” “summary” of this topic tends to be rather gigantic.

Though I did receive a minor in both Economics and Political Science while completing my undergraduate degree in history—my graduate work has all be in theology and philosophy.

I should say that this is my example, which I have offered to maximize simplicity and clarity. I am sure that Hegel’s account of such a development would be much more complex and nuanced. But I think this example shows the main thrust of his thinking.

cf., among others, The French Revolution

It’s important to note that many academics employ “Marxian” theory without necessarily subscribing to Marxist political beliefs.

This is the point at which I brace myself for the reactions of my perturbed Marxist brothers and sisters. Don’t worry, I subscribe to Jacobin too!

I think it is important to note, however, that one can accept Marx’s description of political economy without accepting the full suite of his prescriptive ideas for how a society might be structured. I say this knowing that Marx himself tried to collapse this descriptive/prescriptive distinction, arguing that his vision of socialism and then communism wasn’t really a political program at all, but only a scientific description of what must come to pass. My own view though is that this was always a bit of a red herring, as Marx was trying to avoid being lumped in with the “utopian” socialists of his day, and also a point at which Marx was rather too confident of the precision of his description.