Last week, we dove into the turbulent waters of dualism. I focused my time there pointing out that “dualism” is, as the smart kids say, an overdetermined term: there are (at least!) four different meanings to dualism: what I called 1) ontological dualism, 2) theological dualism, ditheism style, 3) theological dualism, Barthian style, and 4) phenomenological1 dualism.

Attentive readers may remember, however, that I began that post on dualism asking a question about something else entirely—non-dualism. Although I did touch on non-dualist responses to the various modes of dualism outlined, we didn’t dig deeply into it there—so we shall today.

As I pointed out at the top of last week’s post, non-dualism is a trendy, popular word today, especially in many spiritual-but-not-religious spaces who are looking for alternative approaches to spirituality. Many in the west today, both conservative and liberal, tend to act as if the only options are mega-church Christianity or new Atheism. Non-dualism, with its air of mystery, seems to offer a refreshing alternative to both.

Considering that we offered 4 different modes of dualism, one might assume/worry that we will have to investigate 4 different modes of non-dualism here. Fortunately for you, my intrepid but time-strapped reader, things aren’t as bleak as that. Although there are non-dualist philosophical approaches to all 4 modes of dualism outlined, here I want to focus on just two.

Monism(s): Ontological Non-Dualism

Let’s begin where we left off last time. When we westerners talk excitedly about non-dualism today, you may notice they are very often rather vague about their terminology. Frequently they will say that non-dualism is the simple teaching that “everything is actually one”, that the “distinctions between me and others are not real”, etc. My own view is that they are often conflating two of the different modes of dualism in such discussions, and so the non-dualist answer they provide ends up being confused and vague. As you will see, though, I don’t take this as a reason to reject non-dualism—quite the contrary! But as with all things in life, I think some clarity will help.

At first glance, non-dualism mostly sounds like an ontological claim: “all things which seem to be different are actually one thing”, for example, sounds like a rejection of what I called ontological dualism. But right off the bat, we need some more clarity.

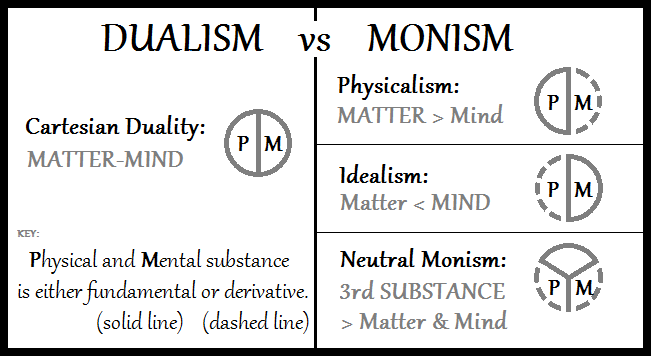

We saw last time that, in its most common form(s), ontological dualism claims that there are two basic kinds of “stuff” or substrate, out of which all existent things are made. Likewise, a non- or anti-dualist alternative claims that there is only one kind of stuff out of which all existent things are made. This handy graphic from Wikipedia might be of some help:

Another way of putting this is that dualism, on the one hand, or ontological non-dualism (generally referred to, as in the graphic above, as monism), on the other, are different theories about what kind of things exist: either mental/conscious/phenomenal things only (idealist monism), material things only (materialist monism), both kinds of things at once (substance dualism), or some other unknown kind of stuff, which itself is expressed in both mental and material kinds of things (Russellian neutral monism).

But notice that each of these options talks about what kind of things there are, but not about how many things there are in total. All 4 of the basic ontologies listed above will tend to assume that there are, in fact, at least many hundreds of trillions of different things in the cosmos. They just disagree about what those things are made of, at the most fundamental level.

As an example: a materialist (and, for that matter, really everyone) will agree that both nails and screws can be made of the exact same kind of metal. Indeed, one could cast a collection of 1,000 nails and then 1,000 screws out of the same pool of molten steel. They would all be made of the same material substance, yet there would be 2,000 unique entities.

But our non-dualism enthusiast above said that non-dualism was the idea that everything is actually one, that all distinctions are actually illusory, that the divide between me and others was false, etc. But as we have just seen, monism, of whatever variety, doesn’t necessarily make any such claim. Just because my car and my stapler are both made of metal doesn’t mean that my car is actually a stapler.2

However, our non-dualism enthusiast is not necessarily wrong in their assessment of non-dualism. While it’s true that no version of ontological monism is necessarily committed to claiming that there is, in fact, only one actual thing in existence, such an option is still on the table. But to see how, we will need to switch gears from our ontological discussion to our phenomenological one.

Phenomenological Non-Dualism

As discussed last week, phenomenological dualism is the claim that the subject, that is, the “viewer” or “thinker”, is distinct from the objects, that is, the contents of experience that are “viewed” or “thought of”. For example, if I am thinking of a red apple, “I” is distinct from the “redness” and “appleness” that are being seen and/or conceptualized.

Now, phenomenological dualism isn’t really a term you see very often, because it’s more or less the default, common sense “folk psychology” view of conscious experience. Most of us, perhaps nearly all of us, are raised to think of ourselves, as conscious subjects, as distinct from the objects we encounter in our world.

But this term, phenomenological dualism, is necessary, because the opposite idea, phenomenological non-dualism, very much is a common term (in certain philosophical circles), and it’s an incredibly interesting, sophisticated, and provocative idea.

Phenomenological non-dualism is one of those ideas that seems to crop up repeatedly in various human cultures, so it probably wouldn’t be correct to trace it exclusively to one time or place.3 That said, I think it’s pretty uncontroversial to argue that the earliest written systematic expression of this idea occurred in Indian philosophy, beginning some time around 500 BC, at the latest, with the Upanishads (a loose collection of texts which are themselves generally included under one of the four Vedic collections). This idea continued to be honed and analyzed further, especially in the work of Shankara around 700 AD. It then blossomed into a variety of subtly but importantly different versions under thinkers like Ramanuja, circa 1100 AD.

(This post is not meant to be a systematic presentation, even in summary form, of Shankara’s system of thought. I am using him as a jumping-off point because I think his approach is rather clear, especially as it begins with phenomenological insight. I am no expert in Advaita Vedanta, not even by a long shot! Indeed, my reading, apart from the principle Upanishads, has been in secondary texts.4 I am still very much a very early-stage student of this set of philosophical systems. What follows is definitely an amateur-level engagement with Shankara. But I am using that engagement to make some broader points about non-dualism in general.)

The basic argument for phenomenological non-dualism is actually quite straightforward: we think of our perceptions (like the bare perception of redness) and our concepts (like the concept of an apple) as separate from us, but in fact, both of these things are really events within the field our own consciousness.5 A certain patch of our visual field will look red one moment, but if we move our head, now it will be green, or beige. If we close our eyes, it will become pitch black (or, colorless, depending on how you want to think about it). Of course, the color hasn’t gone anywhere, rather, our mind has interpreted the information provided it differently. Redness is something our mind does when it thinks there is something with the quality red in our visual field. This can be because our optic nerve really is signaling the presence of something with the right frequency of light “out there” in the world, but it could also be during a dream, a hallucination, or just when we are intentionally imagining things (for example, when some weirdo on substack demands that you “think of a red apple”).

The same is true of all the other phenomena we experience. I covered the basic understanding of this idea in my first post, so if you aren’t quite sure you’re picking up what I’m laying down, you may want to go read that. The concept of an apple is a sign that our mind makes to itself that allows it to distinguish between different kinds of things in our world. For example, for something to be an example of that which our concept of an apple is a category for, it must have shape, size, texture, color, smell, etc. within a certain range. Apples can be red, yellow, and green, for example. Perhaps we could also encounter a purple apple. But if someone presented us with a transparent apple, we would probably be suspicious about its appleness. It might be a sculpture in the shape of an apple, but it would not actually be an apple as such. Likewise, that logo on the front (back?) of your laptop is something like a 2-dimensional representation of the shape of an apple, but is not an apple. Indeed: you may refer to your phone as an “Apple” as opposed to an “Android”, but you don’t actually mean the fruit apple. The same word is being used to refer to many different concepts.

The point is, all of this consideration of the nature of appleness occurs within consciousness. The rules for what constitutes a real apple are rules we decide on and apply for ourselves. Admittedly, we get most of these rules from the language community or communities of which we are members, but even so, the event of my thinking of an apple is rather obviously an event within my consciousness. As I insisted back in my first post, few if any people would argue that my concept of an apple is actually itself an example of a real apple; I can’t eat my concept of an apple, after all.

To the extent that I consider the field of my consciousness more or less coextensive with my mind, and if I think of my mind as more or less what “I” am, then, it’s not hard to conclude that all the contents of my consciousness are really just parts and pieces of what I am, elements of my very own self.6 An object of consciousness, in other words, is something that that consciousness itself does, or even is; it is a “thing” that consciousness generates as a sign to itself and within itself, which is also “made of” consciousness, as it were.

This is all a bit wordy and abstract, but I still think (and very much desperately hope) that what I’ve outlined in the last few paragraphs is, indeed, relatively uncontroversial, even if it’s a way of thinking about our mental lives that will seem new and odd to many. I think even an ardent materialist would be willing to admit that, when engaging in phenomenological analysis, the idea of an apple is something that the mind does more or less within itself, for itself, and as itself—even if that materialist would, at when engaging in ontological analysis, want to reduce that mental activity to something non-mental (that is, argue that ultimately the idea of an apple is nothing more than electrochemical activity in the brain). So long as we are still doing phenomenology, that is, considering how phenomena relate to each other within the immediacy of our own consciousness, and not attempting to ask how those phenomena do or do not relate to things “out there” in the world, then I think we are on solid ground (if you are interested in learning more on this important demarcation between phenomenology and other forms of philosophical reasoning, you may want to look into the critical idea of bracketing introduced by Edmund Husserl).

From Phenomenology to Ontology—and Beyond!

But of course, philosophy itself can’t be hemmed in by any such limitation. Although my own belief is that solid philosophy must always be built on phenomenology, and really, needs to begin with phenomenology, philosophy as such can end with phenomenology alone. Phenomenological non-dualism, taken on its own, may just be a subtle and interesting way of refining our analysis of consciousness as such. But once we move from purely phenomenological analysis and stray back into the broader world of philosophy, phenomenological non-dualism raises radical implications.

This is certainly the path that Advaita Vedanta philosophy, the school of thought pioneered by the previously mentioned Shankara, takes. Advaita begins with the recognition that the contents of consciousness are events within consciousness, and therefore ultimately not distinguishable from consciousness in general—as outlined above. In this way, Vedanta is grounded in what westerners now call phenomenology—even though it never uses that term, of course (indeed, it would take us westerners until the 18th century to even formally recognize this approach to philosophy, whereas Indian philosophers were doing it at least 2,000 years prior.)

Advaita may begin with phenomenology, but it certainly does not stop with phenomenology. First off, Shankara saw no reason to relate the phenomena of consciousness with any kind of “external” noumena beyond it. This is the first way in which he “ontologized” his phenomenological discoveries. In western terms, he embraced ontological idealism, which we touched on above (check out the graphic up there if you’re a bit lost). Idealism is a broad category for a vast number of different ontological systems, but at its core, idealism argues that only consciousness/“mind” is real, that the objects of consciousness don’t really have any kind of extra-mental material referent, but are rather objects of consciousness only. To simplify a very complex argument, Shankara noticed that only phenomena are available for, or “present” to, consciousness, and he drew the conclusion that that meant only consciousness, and the objects “made” of consciousness, are meaningfully real.

But that’s not all: Shankara, like many before and since, recognized something interesting about our conscious experience: if we try to abstract consciousness as such from the contents of consciousness (that is, if we try to firmly distinguish the “I” from the objects the I perceives, thinks, feels, etc.) through, for example, contemplative or meditative practices, to the extent that we succeed, we are left with bare consciousness itself. A consciousness without any contents, a subjectivity without any objects, would be something like bare awareness. Try to imagine being conscious, without being conscious of anything at all.

Such a state is pretty hard/completely impossible for most people to even imagine, much less actually realize. Of course, some particularly well-disciplined people like Buddhist monks or Hindu gurus (not to mention plenty of Christian monastics and Islamic Sufis, and plenty of others besides) claim to have indeed achieved such a state of consciousness. Nevertheless, such a state seems at least theoretically unproblematic: we might draw an analogy between a mind in perfect meditation and a television that is turned off: all the pieces for the arising of phenomena (perceptions, feelings, concepts, etc.) are there, but nothing is currently being displayed.

Shankara, though, took a big step. He recognized that, though we can certainly distinguish between, say, different human bodies—this one is tall, this one is short, this one is male, this one is female, this one is dark-skinned, this one is lighter-skinned, etc.—and that we can likewise distinguish between different collections of occurrent mental states—this one is thinking in English, considering a red apple, and feeling hungry; whereas this other one is thinking in Sanskrit, considering a mango, and feeling sleepy, etc.—if we abstract away both awareness of the body, as well as the other phenomena of mental life, we have a bare consciousness which would seem to be universal to all people. That is, once consciousness is stripped of any objects, it would be hard to distinguish my consciousness from your consciousness, because the way we distinguish different consciousnesses is by what objects appear in them. (Not everyone would agree with this, of course! And Shankara himself obviously offered a much more robust argument than my brief summary above. But for now I want to simply follow the basic version of Shankara’s logic.) My identity as a particular human really seems to resolve to nothing more than what the objects of my consciousness are (including the ways in which I am aware of my body).7

Shankara recognized this seeming universality of bare consciousness, and accepted an obvious, if radical and unsettling, consequence: if my bare consciousness is functionally indistinguishable from your bare consciousness, they must actually be the same consciousness. Just like in his move to idealism, here he takes what he discovers phenomenologically: “I seem to achieve a state of undifferentiated consciousness when I meditate”, and draws an ontological conclusion: “if two different instances of undifferentiated consciousness are not distinguishable from each other, they must actually be the same”. This is a further ontological application of the insights he had already developed.

Finally, Shankara made a theological maneuver: since bare consciousness itself seems to be the universal subject of all consciousnesses, and since all the objects of consciousness are ultimately only things that consciousness does or forms that consciousness takes, Shankara reasoned that bare consciousness itself is, in western terminology, God—that is, the fundamentally real, absolute source of all apparent reality.8 The contents of the individual consciousness are reducible to the that individual consciousness; each individual consciousness is actually one general consciousness; this general consciousness is the supreme, ultimate, and absolute source, ground, and reality of all things. (Things do get more substantially complicated, especially in the relation between Brahman and Atman, and all their forms. But I don’t want to go down that rabbit hole in this particular post.)

In short: Shankara is a non-dualist all the way down: he begins with phenomenological dualism, then moves to ontological dualism, and finally affirms not only monotheism, but also the opposite of Barth’s theological dualism as well: for Shankara, our own deepest sense of self, bare, undifferentiated consciousness as such, just is the supreme, ultimate, absolute reality (in our terms, “God”). For Shankara, then, everything really is, top to bottom, one.

Not everyone, of course will accept Shankara’s series of conclusions. Indeed: you, gentle reader, may have found yourself balking at any one of the steps above. You would not be alone.

Non-dualism vs. non-dualism

Indian philosophy is a vast, vast cosmos of different systems of thought. It’s hard to even begin to describe the diversity of positions on offer. The gap between Nyaya, for example, and Samkhya—and then between those two and the various positions of Vedanta—is huge. So it would be a massive error to suggest that Shankara’s position is somehow the Indian position. It’s not even the agreed-upon position of Vedanta, much less those other approaches to Hindu thought, nor to mention the non-Hindu approaches of, say, Buddhist or Jainist thought.

But for the moment, let’s just consider one philosopher who disagreed with Shankara within the field of Vedanta thought itself. Ramanuja was born roughly 4 centuries after Shankara, and he would come to lead a different school of Vedanta. Whereas Shankara’s school is titled simply Advaita—literally “non-dualism”—Ramanuja would found the philosophical school referred to as Vishishta Advaita—literally “non-dualism with distinctions”. This label gives us some clue to Ramanuja’s system, and in what ways he differs from Shankara.

I don’t want to dive into the details of Ramanuja’s system, not only because this post is already very long, but also because my grasp of it is severely limited—I am still new to reading Vedanta, and for the most part have read about and from the advaita tradition. I definitely will have more to say about Ramanujua, and other Vedanta thinkers who contested Shankara’s advaita position, in later posts. (Once I get quite a bit more reading done!)

But there is one major takeaway from Ramanuja’s system that I want to highlight. Though he also endorsed “non-dualism”, his non-dualism had, as the Sanskrit name for his school says, distinctions. Whereas Shankara was a non-dualist all the way down—he embraced non-dualism along all 4 modes of analysis we looked at in my previous post on dualism—Ramanuja was more circumspect. I think ultimately he embraces both a version of phenomenological non-dualism, in which the objects of consciousness are in some way reducible to that consciousness—and a version of theological non-dualism, in which all things are reduced to “God” (in the western philosophically monotheistic sense of that word), but his ontological system allowed for more genuine distinctions between various entities in the world (his ontology, if it is non-dualist, is a complicated non-dualism).

But the point is this: one can accept non-dualism in one level of analysis, without necessarily accepting it in another. Furthermore, one can accept a broadly non-dualist position on a given topic, and yet disagree about the specifics. The relationship between phenomenological non-dualism, on the one hand, and ontological non-dualism, on the other, can be especially fraught, and there are many ways of trying to link or de-link them.

What I have been driving at, then, in both the previous post and this one is that if someone tells you they have embraced non-dualism, but they don’t offer any further details, it is likely that they haven’t really looked deeply into these questions. That’s OK! There’s always more to learn in life. But non-dualism cannot be a solution to anything, whether philosophical, spiritual, or practical, if it is left as a wildly vague signifier that could mean almost anything. It is, I think, all to easy for certain spiritual-but-not-religious types to claim non-dualism for themselves, but then not explore what that means any further. As my verbose nerdiness over the last few thousand words proves, I think that’s an error. (And as a student of Levinas, I worry about the implications of an insufficiently critical non-dualism…)

It’s an error not only because such vague references to non-dualism don’t ultimately amount to much, and also contribute to a sort of fetishization of “eastern” spirituality that I think is often harmful both to the east and the west, but I think its real harm lies in the fact that this vague, incurious embracing of “non-dualism” leads to people not actually discovering what non-dualism is all about. I actually think that non-dualism, broadly speaking, offers important resources to modern people, both philosophically and spirituality—as I plan to discuss in further posts on this blog. But for us to use those resources, we will have to really dig into them deeply. Surface-level enthusiasm about an exotic-sounding term will not be nearly enough.

And this point is only brought into sharper relief when we recognize that, actually, non-dualism isn’t an idea limited only to traditional Indian philosophy; indeed, as I will discuss in future posts, we may find that west and east meet readily on the ground of non-dualist thought, even if the western history of non-dualism has largely been obscured to most people in the modern era. (Get ready for some Plotinus in the future, my friends!)

But this post now (mercifully) draws to a close. I thank you for reading this far, and I hope the discussion above has been interesting and worth your time. As always, if you have thoughts, reflections, or critiques, please feel free to leave a comment.

Remember: every time you read the word “phenomenology”, Edmund Husserl’s transcendental ego gets another set of wings!

Now an in-depth discussion about the important distinctions between these claims would mean a long discourse about things like “form” and “matter”. I would likely have to indulge in an extended tangent about Thomas Aquinas and his beloved hylomorphism. But this post isn’t a detailed discussion of applied ontology. I want to stay “zoomed out”, big picture.

Indeed, as I hint at near the end of this piece, non-dualist ideas crop up all over the place, including in classical Greek philosophy.

I’ve drawn my understanding primarily from:

Shree Purohit Swami & W.B. Yeats, The Ten Principle Upanishads

S. Rhadikrishnan, Indian Philosophy, volumes 1 & 2

David Bentley Hart, The Experience of God

Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj, I am That

Bede Griffits, Vedanta and Christian Faith

Note that I will continue to use the word “consciousness” below to refer to the field in which phenomena appear. The word is somewhat fraught in English-language philosophy of mind, as it can actually refer to many related but different things. While there are some more technical terms that can be helpful (such as “phenomenality”, to say nothing of some technical Sanskrit terms), that jargon can also make discussions of this topic much less accessible. So I will continue to use “consciousness” below, but please be aware of the potential confusion and vagueness that can result.

Of course, plenty of people might question some of the premises I just loaded into that statement. And I do want to pursue deeper questions about mind and self, in a later post. For the time being, though, I want to assume that what I laid out is at least a reasonable position, and one that many would accept, even if it’s far from universal.

This is one of the principle reasons that so many spiritual and philosophical systems, most obviously Buddhism, are so suspicious of individual identity, since if it’s really just the collection of mental states I have or can have, then it is something that is always changing.

The terminology in Sanskrit is far more complex; the term paramatman is probably the best one to reference here, which means something like “the supreme/ultimate self”, with the English term “self” here meaning something more technical than it normally does in English. Meanwhile, the English “God” is often used in translating Sanskrit to refer to entities that most western monotheists would not think are properly and fully divine.

Thank you for this illuminating post. Especially in our time where, for lack of a better word, "Neo-Vedanta" has become widespread, it's quite important to actually get an understanding of the delicate phenemonological and metaphysical and spiritual nuances of Neo-Platonic and Vedantic philosophy. Ramanuja, for me, is much more constructive and palatable for me, but even so, the idea needs to be dispelled that all that is required for moksha or hit the epistemic switch to "witness consciousness" by simply thinking I am brahman is a gross oversimplification of the matter. It's kind of like trying to explain the intelligence of neo-platonism and the intellect--especially in Gregory of Nyssa's Christian understanding that our nous or intellect is a share of God which though a share is indefinable and limitless, in essence. Thanks for this.

Talking about East meets West I was thinking about doing a post on Pyrrho. But anyways an excellent and informative read!