Postmodernism vs. Postmodernism, Part 2: Ontic vs. Epistemic Postmodernism

Or: Bad Pomo vs. Good Pomo

Last week, we took a look at the basic origin of postmodern philosophy, exploring how Kant’s distinction between the phenomenal and the noumenal set the stage for a crisis in modernist (i.e. more or less Enlightenment-era and, sometimes, post-Enlightenment) philosophy. I suggested at the end of that piece that the main reaction to this crisis—what we generally call postmodernism—took two distinct paths, one of which is the better-known (and frequently attacked), the other of which gets much less attention (but I think should get much more). So let’s dive right in1 (though if you haven’t read Part 1 and you aren’t that familiar with Kant’s work, you may want to read that first).

Western philosophers in the 19th century, who took Kant’s distinction seriously, were indeed in an intellectual crisis, for if the phenomena of our thinking lives—sensory impressions, concepts, the reasoning that binds them, etc.—have no guaranteed access to the noumena of reality, of things as they are in themselves, then it would be easy to give into despair: perhaps our thinking makes no contact with reality. If Kant is right, we can’t actually ever check or verify whether it does, since any new evidence we could evaluate would be, of course, evidence that we gathered with our senses and used our reason to organize into concepts—all evidence of the noumenal must become phenomenal for us to consider it at all.

From one perspective, then, post-Kantian philosophy found itself “locked in” to the mind. They wanted to say true things about reality, but had lost confidence that they could do so. What does an aspiring philosopher do in such dire straits?

Ontic Postmodernism

One response is to accept Kant’s distinction, but then to flip Kant on his head: one could accept that indeed thought has no access to any reality beyond itself, but instead of accepting that this means there is some kind of un-cognizable noumena “out there” that transcends and outstrips thought, one might insist that if the mind cannot secure access to any kind of mind-independent reality, it must be the case that no such reality actually exists.

This view contests and overturns modernism on three major fronts: first, it obviously agrees with Kant’s critique of modernism’s assumption that reality (noumena) was available to, or perfectly reflected in, thought (phenomena). But it then leapfrogs well beyond Kant, in arguing that the solution to the conundrum he introduces is to simply deny that there is any noumena “out there” for our phenomenal lives to correspond to. Instead, there is only the phenomenal. But this comes with a serious implication: if there is no noumenal world, no universal and shared reality that each of our phenomenal lifeworlds correspond to, then there is really no shared, universal ground of our existence and experience whatsoever. According to this position, there is no shared conduit by which my thought and your thought can come to some kind of agreement on what truth is, since there just is no objective ground of truth for us to agree on.

This is the first model of postmodernism, and I prefer to call it ontic postmodernism, because it takes Kant’s phenomenal/noumenal distinction to have ontological implications, namely, that being as some kind of mind-independent reality can’t be said to really exist. Instead, there is only the endless play of thought, which is itself tethered to nothing other than its own (epistemological) rules and preferences. On the view of ontic postmodernism, objective reality collapses into the purely and fully subjective.

A bleak perspective, to be sure. But things get much worse.

Intensifying the Crisis

The next problem is obvious, though easy to overlook: in evaluating our own thinking, we have access to our perceptions, our concepts, our reasoning. And the conclusions we arrive at will likely seem obvious and even necessary, since they are precisely the conclusions that seem to result from the particular mix of perceptions and concepts we personally hold.

But other people’s perceptions, concepts, and reasoning process are not immediately available to us. We know our own perception of redness, for example, more-or-less immediately. The perception of redness is just there, in our consciousness, in the field of our phenomenality, without our having to search it out or ask any questions about it. It is a quality that occupies our consciousness in a direct and undeniable way. When I feel hungry, I have no doubt that I feel hungry. The feeling is right here, undeniably present in and to and for and indeed as my consciousness.

But other people’s perceptions are simply not available to me in this way. (This is hardly controversial, but the implications of this simple truth end up being quite severe.) If I want to know what you are perceiving or feeling, you have to tell me, either verbally, in writing, through sign language, or through some other mode of communication, perhaps through facial expression, what you are perceiving or feeling. But remember that this means that the immediate reality of your perception or feeling has to be transformed into phenomena for me. In this way, then, your phenomenal experience is necessarily a noumenon for me, even though for you it is the most secure phenomenal experience possible.

But if your mental life is a noumenon to me, if it is ultimately unknowable, and if I commit to the idea that the best solution to Kant’s phenomenal/noumenal distinction is to simply deny that the noumenal has any reality whatsoever (that is to say, if I accept the ontic postmodern perspective), then the obvious implication is that other people’s mental lives don’t have any reality for me. Perhaps there really is some other thought-thinking-itself “out there”, but, according to the ontic postmodern resolution of Kant’s distinction, I could never know any such thing, can secure no contact with it, and could only know anything about it by transforming it into my own phenomenal life. In this way, other people are, at best, simply content for my own thinking, (mental) objects which I can interact with—or not—according only to my own preferences and goals.

Now, my goal in this two-part piece is to trace the logic of the development of postmodernism in general, and not to provide any kind of close analysis of any particular thinker. Even so, gentle reader, I imagine you’d like some examples of ontic postmodernism. In many ways, the examples abound; as I suggested earlier, this mode of postmodern thought is, I think, the dominant one, and it’s certainly the version of postmodern thought that gets the most attention. But I would say that Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger are probably the best exemplars of this perspective.2

Nietzsche is, I think, the most obvious representative of this perspective. Consider, for example, Nietzsche’s famous claim that “God is dead…And we have killed him”. This is not just a claim about the (supposed) irrelevance of one idea of divinity within Western Jewish and Christian thought—Nietzsche is claiming the death of much more. For Nietzsche, the death of God is also the death—the intellectual impossibility—of any possible metaphysical ground beyond the self, because Nietzsche recognized the implications of Kant’s distinction, and took the ontic postmodern path I outlined above: for him, there is no noumenal reality to anchor ourselves to—not God, not morality, not even our relationships to other people. In this abyss, it’s not surprising that Nietzsche could find only is own will to power as a new locus for organizing his identity and his goals. In the absence of any idea of a reality beyond the self, the self must become a new and awesome god: ontology collapses into one’s own phenomenal frame.

So that’s the ontic postmodern path, as I would categorize it. Nietzsche’s expression of it is, I think, the most stark, but it crops up all over the place in 20th and 21st century thought, though often more implicitly than explicitly.

Having read all of that, you might be thinking that all the people who reject postmodernism are on to something—the ontic postmodern outlook looks bleak indeed, and it seems like it could easily lead to justifications for all kinds of horrors, philosophical and ethical! Now, certainly, many folks respond to this threat by insisting that we need to get back, to retrieve something that has been lost, whether a return to modern philosophy (this is the basic maneuver of many liberal secularists) or to a pre-modern philosophy (common among many religious types). Now, I myself am sympathetic to such moves, to an extent (especially the pre-modern move), but my own view is that we can’t just dodge Kant’s distinction. But this raises the question: is there a way to accept the gap between the phenomenal and the noumenal without embracing Nietzschean nihilism?3

Yes, there is!

Epistemic Postmodernism

If we return to Kant’s distinction, we should remember that Kant himself was making an epistemological, not an ontological claim: he simply said that the thinking subject cannot secure knowledge about the world beyond thought, not that such a world didn’t exist. It was the ontic postmodern maneuver that made ontological (that is to say, claims about what kinds of things truly do exist) claims in trying to resolve Kant’s distinction, to avoid dealing with its messy implications. But what if we accepted Kant’s distinction on its own terms, as an epistemological claim (that is to say, claims about how we can try to achieve trustworthy knowledge or how we should try to organize our claims to knowledge) alone?

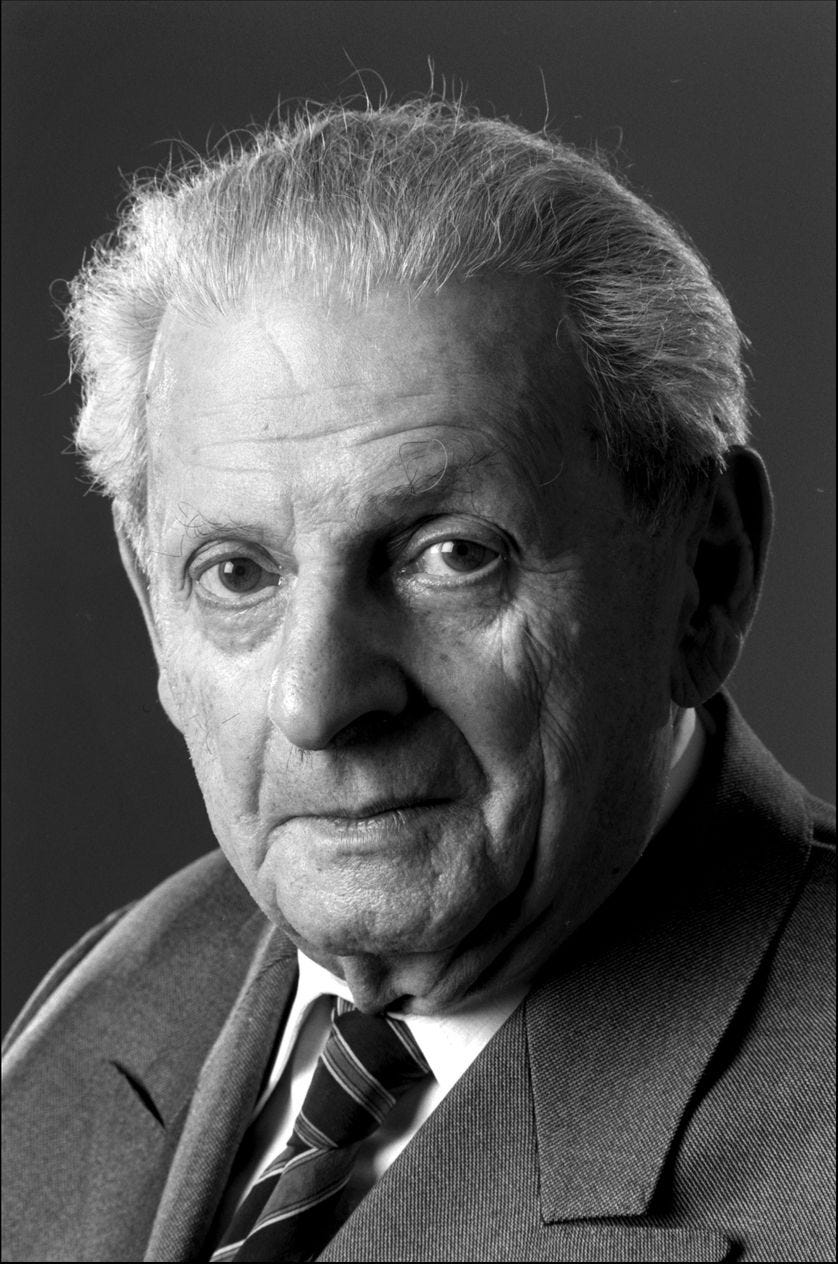

The good news for us is that, in fact, some philosophers have already done so. I am sure there are many names that we could cite here, but I want to focus on the only one I can claim to have any meaningful knowledge of: Emmanuel Levinas.4

Levinas was (among many other things), a student of Edmund Husserl’s, essentially one of the “2nd generation” phenomenologists. He studied alongside Heidegger in the early 20’s, but ended up taking a very different path in philosophy. While Heidegger had his “Aristotelean turn” in the late 20’s, and attempted to turn phenomenology into yet another universalizing ontology (one in which the single thinking person, Dasein, is able to discern the “Being of” other “beings” through careful philosophy), Levinas instead took Husserl more seriously and tried to develop and expand his thought.

Levinas began with and remained loyal to Husserl’s method of epoche, of “bracketing” any question about the relation between one’s perceptions and thoughts, on the one hand, and the reality to which they supposedly point, on the other (that is to say, under the discipline of Kant’s distinction), Levinas sought to ask what exactly phenomenology could discover metaphysically, under these limits. Notice that, under Husserl’s epoche, the noumenal’s reality is not denied, is not erased, is not eradicated—as it effectively is under the ontic postmodern method—but is rather set aside. Husserl took Kant at his word epistemologically: we can’t know whether our thought corresponds to the reality “out there”, but that neither means that it really is or really isn’t out there. We have to remain agnostic, rather than either credulous (as in modernism) or unreasonably and antagonistically skeptical (as in ontic postmodernism).

For Levinas, this was the crucial key. What if we accepted that our phenomenality, our consciousness, could not access noumenal reality, but then simply concluded that reality was indeed bigger, broader, deeper, and indeed maybe even realer than our limited consciousness? This take’s Kant’s distinction just as seriously as the ontic postmodern move, but keeps Kant on his feet, head up: we want to know reality, but reality outstrips our ability to know. On this view, the proper response to the unknowability of the noumenal is not an arrogant rejection of its real-ness, but rather the embracing of epistemological humility: there is more to this world than I can see, know, or even imagine. For Levinas, the world beyond our thought is indeed marked by the phenomenal attribute of alterity, “otherness”: the noumenal is truly other than me and my consciousness. But this is not a reason to reject its reality—just the opposite! In the face of the noumenal, that other which I cannot reduce to my own consciousness, I must humbly set a limit, a boundary, to the acquisitiveness of my own thought. I must accept that there is an unconquerable horizon to my thought: Here, but no further.

Losing Ourselves in the Face of the Other

For Levinas, the truthfulness, or at least the likelihood, of this perspective was best illustrated in how this epistemic postmodern view differed from the ontic postmodern view in how it related to other people. Above, we discussed the problem for ethics under the ontic postmodern framework: if other people are purely noumenal to us, only available to us to the extent that we transform them into phenomena for us, then other people’s independent reality dissolves into an effective solipsism. But if we instead see the noumenal not as nothing more than the phenomenal mark of an absence, but rather a way of signifying how reality outstrips phenomenality as such, then other people can be understood as realities that transcend the limits of our thinking.

This understanding of Kant’s distinction renders other people not as mere objects of thought, entities we can bend to our own will and preference, but rather as realities to whom we owe something, manifestations of the reality beyond us that peer through the veil of phenomenality and remind us that, though we may not be able to access our shared reality in thought, that we nevertheless do live there, in a mode of our own existence that we cannot even grasp within our own subjecthood.5

For Levinas, then, when we stand face to face with another human being, a fellow subject, that face6 gives itself to us as a phenomenon that marks a pure noumenon: the face is known to us, but it signifies a reality which is never present to our consciousness, the “inner life” of the other person. Though we can imagine that inner life, we can—as Kant so assiduously reminded us in the phenomenal/noumenal distinction—never actually enter it. Instead of seeing this as a reason to reject the reality of that ungraspable other, Levinas does exactly the reverse: recognizing that other people are not available to us in their depth means we must recognize the severe limits of thought’s grasp on reality.7

This, then, does lead to Levinas’s famous dictum that “ethics must be treated as first philosophy”, but it’s crucial to see that he arrives at this appreciation of ethics through a purely phenomenological process, a phenomenological delimitation of any possible phenomenology. Ethics is the result, not the starting point, of Levinas’s project.8 This is epistemic postmodernism, a version of postmodernism that gets much less attention—indeed, a postmodernism that I think many people, already weary of “postmodernism”, really don’t know about at all. It’s a postmodernism that in many ways directly addresses all of the major complaints that so many have about our flat, hopeless postmodern world.

For Levinas, Kant’s distinction is the very ground of a “re-enchantment” of the world, because on his view, the world constantly signifies to us the not-present (to our consciousness) real presence of a staggering richness of noumenal reality. Indeed, I think it’s fair to say that the best translation of Levinas’s French altérité is not the clunky transliteration “alterity” or even “otherness” but rather holiness: being set apart. Levinas’s postmodernism, in other words, secures not only a postmodern ethics, but also postmodern theology and, indeed, even postmodern metaphysics,9 even if he does so by traveling the lonely and anxious road of postmodernism, rather than by simply trying to retreat to a time before Kant’s world-shattering Critique.

There is, of course, much more to say about both modes of postmodernism, their interaction, and their utility. But this post is already (way too) long, so I will end here. I hope, at least, it has given you, dear reader, food for thought as we consider how to navigate the wide sea of our postmodern moment. Thanks for reading.

Dear, gentle, forgiving reader: I have been endeavoring to keep these posts under 2,000 words. In this post, though, I have utterly failed to do so, as I wanted to address both modes of postmodernism in one piece, rather than breaking this into yet more pieces. I hope your patience is matched only by your

I am sure that many people would want to contest my categorizing of these thinkers as “ontic postmodernists”, especially Heidegger. (And other readers may have other names they’d like to add to this short list). I’m certainly on expert on either thinker, but I do think they both exhibit the basic metaphysical position I have outlined as ontic postmodernism. I have neither the space here, nor the expertise in scholarship, to get into further detail at this time, though.

In fact, Nietzsche didn’t think of himself as a nihilist, and indeed saw himself as fighting against nihilism. Indeed, in many ways, the ontic postmodern perspective is a re-inscription of modernist universalizing thought, only redefining the universal reality as one’s own consciousness. I have more to say about this below.

Two others that do deserve a mention, I think, are C.S. Peirce and Richard Rorty. Kant himself, I think, also certainly qualifies.

Levinas, indeed, reminded his readers that we ultimately were totally other (noumenal) even to ourselves; that is, that the reality of our existence was not truly and totally available to our own thinking.

And indeed it is others’ faces that occupy a central place in Levinas’s phenomenological ethics. My own view, though, is that this “face” need not be the literal human face of another’s body—though of course this face does qualify. But any phenomenon that suggests that other-and-more-than of another person’s full reality can function as the “face” here.

To borrow a phrase from a different postmodern thinker, epistemic postmodernism simply insists that “the map is not the terrain”: our mental map is not identical to the terrain it describes, just as the globe sitting on your desk is not literally planet Earth. Ontic postmodernism, on the other hand, banishes the Earth and pretends that the globe is all their is (if I may be allowed a rather polemical summarization).

This is something that many people who seem to cite, rather than read, Levinas’s work often get wrong, in my opinion. But that’s a topic for another time.

Indeed, Levinas explores some implications for these topics in some of the appendices of his Totality and Infinity.