Postmodernism vs. Postmodernism, Part 1: The Birth of Postmodernism

A brief genealogy of postmodernism

“Postmodern” is one of those words we often hear, but which rarely gets defined. This is already a suspicious state of affairs, but when we add the fact that it’s almost always used as a pejorative or accusation which is hurled at one’s ideological enemies, our suspicion should intensify. If we are going to go around trying to disparage each other with 10-dollar words, we ought at least to know what they mean.

Right off the bat, though, let’s set some limits. The first thing to know is that “postmodernism” is used to refer to a range of different human activities: there is postmodern architecture, postmodern painting, postmodern literature, and postmodern philosophy—and I am sure there are plenty of other fields which host postmodern content, as well. Although there are some threads that connect these different kinds of postmodern activity, they are also very diverse: someone could like postmodern architecture, for example, but not like postmodern painting.

This is a substack about philosophy (and also other things, but none of those things are architecture or art), so I doubt it’ll surprise you hear that I won’t be addressing any kind of postmodernism except postmodern philosophy.1 So what is postmodern philosophy?

Now having set this as my task, let me quickly cover my posterior and remind you, gentle reader, that the answer(s) to that question could fill many volumes. But I do think we can arrive at a pretty solid, if still summary, answer in this and the following post. As you will see, I think there are two main streams of postmodern philosophy. One of them is (in my ever-humble opinion) not worth much of our time. The other, though, very much is. But, let us begin:

A Brief Sojourn Into Modernism

The obvious question to ask if we are seeking clarity around postmodern philosphy is to consider what modern philosophy is and/or was. But! I don’t want this post to be 10 million words long. So I am not going to delve into modernist (and pre-modernist) philosophy here, except to give this briefest two-paragraph summary:

“Modern” western philosophy began, more or less, with René Descartes Meditations on First Philosophy in 1641,2 an effort to construct a new metaphysics from his own introspection and reason. Modernism broke with pre-modern western philosophy in many ways, most notably in its effort to not appeal to authorities like Plato or Aristotle, but also on its insistence that philosophical truth was best discovered by the individual looking “within” his own mind and relying on his own application of reason.

Now, modernism, in the guise of the Enlightenment, took many and various paths from the mid-17th through the late-18th century, especially in the work of folks like John Locke, David Hume, Baruch Spinoza, and G.W. Leibniz (to name a few of the rockstars). But though they built on Descartes’ basic method, they all arrived at rather different metaphysical positions. This was a bit perplexing, since the claim had been that this new method should yield some kind of undeniable, self-evident philosophy. Instead, though, we had at least two major camps (empiricism and rationalism—those who focus on sensory input as basic reality vs. those who focus on the rational ordering of reality) and quite a lot of debate not only between, but also among them. The dream of a universally-accepted metaphysics seemed no closer than before.

Kant’s Controversial Distinction

But in the 1780’s, one Immanuel Kant thought that he could probably pull it off. He sat down at his desk day after day, and eventually he had produced The Critique of Pure Reason. The Critique was meant, much like Descartes’ Meditations a hundred and fifty years prior, to establish a new foundation for philosophy. One of Kant’s goals was to show that metaphysics needed both empiricism and rationalism, that each “input” informed the other, but that neither was reducible to the other. This was his great synthesis of the prevailing bifurcation in western philosophy at the time.

But in the process of generating this massive work, Kant also announced what he thought was a crucial delimitation of human epistemology: in discussing how we generate knowledge of the “outside” world, Kant pointed out that our phenomenal experience of a thing (our perceptions and concept of a table sitting in front of us) was not the same as the noumenal reality (of the table itself). I discussed this phenomenal/noumenal distinction before, and I don’t want to belabor it here, but I do think this distinction is absolutely crucial in understanding the rise of postmodern philosophy.

Kant’s distinction between what we know and experience, on the one hand, and reality as it is in itself, on the other, was a big problem for both empiricists and rationalists, since each group, in the own way, wanted to assume that the foundational “information” about reality was available to human thought, even if they disagreed about what that basic information was, what it meant, and what to do about it. But Kant argued persuasively3 that this simply wasn’t the case: our knowledge of the world is determined by our perceptive and cognitive apparatus, and there is no reason to assume that we somehow have the capacity to absorb and properly order all the information “out there” into some perfect representation of the world. Instead, Kant argued, we should assume that the noumenal reality of things-in-themselves is “bigger” and indeed stranger than we are able to perceive or understand.

Now, for Kant, this did not spell the end of human reasoning or knowledge;4 indeed, Kant’s whole goal in humbling human reason was precisely to help us use it better: just because we can’t have perfect knowledge of reality as such doesn’t mean we can’t have any knowledge. Our understanding of reality may indeed be mediated and not immediate, but this need not mean it is just wrong or useless.

But many philosophers of the time were outraged and quite panicked by Kant’s claim. Their assumption that reality was basically transparent to human thought, that the human mind could arrive at immediate (that is, utterly un-mediated) knowledge of reality as it truly is was essential to the modernist/Enlightenment project, and they (correctly, as it turned out!) perceived Kant’s distinction as a serious threat to that project.

In the years that followed, many philosophers sought to put the genie back in the bottle, to insist that, actually, the noumenal reality of things was available to our phenomenal perception and cognition, thereby re-securing the basis of modernist philosophy.5 No doubt the most famous of the early contra-Kantian thinkers was G.W.F. Hegel, whose Phenomenology of Spirit sought to enshrine Enlightenment thought in the form of a universalizing absolute idealism in which the movements of the phenomenal just were the noumena, coming into ever-greater focus as the movement of mind seeking to discover its own truth and identity, through the very dialectic of perception and cognition itself.

But though Hegel himself had immense impact on western philosophy (and certainly deserves plenty of study), his effort to deny Kant’s phenomenal/noumenal distinction was not really successful, at least as measured by the center of gravity in academic philosophy over time. As the 19th century wore on, Hegelian idealism slowly withered,6 and by the mid- and late-19th century, many western philosophers, especially on the European continent, were doing their work within the assumption that Kant was right after all.7

The Modern Postmodernist

Kant is often referred to as the final Enlightenment thinker, the great crowning thinker of modernist thought, who managed to synthesize so many of the strands of modernist thought before him. But if he was the last great modernist mind, I think we must also say that Kant was the first postmodern philosopher, because I think the phenomenal/noumenal distinction is really the heart and engine of postmodern thought.

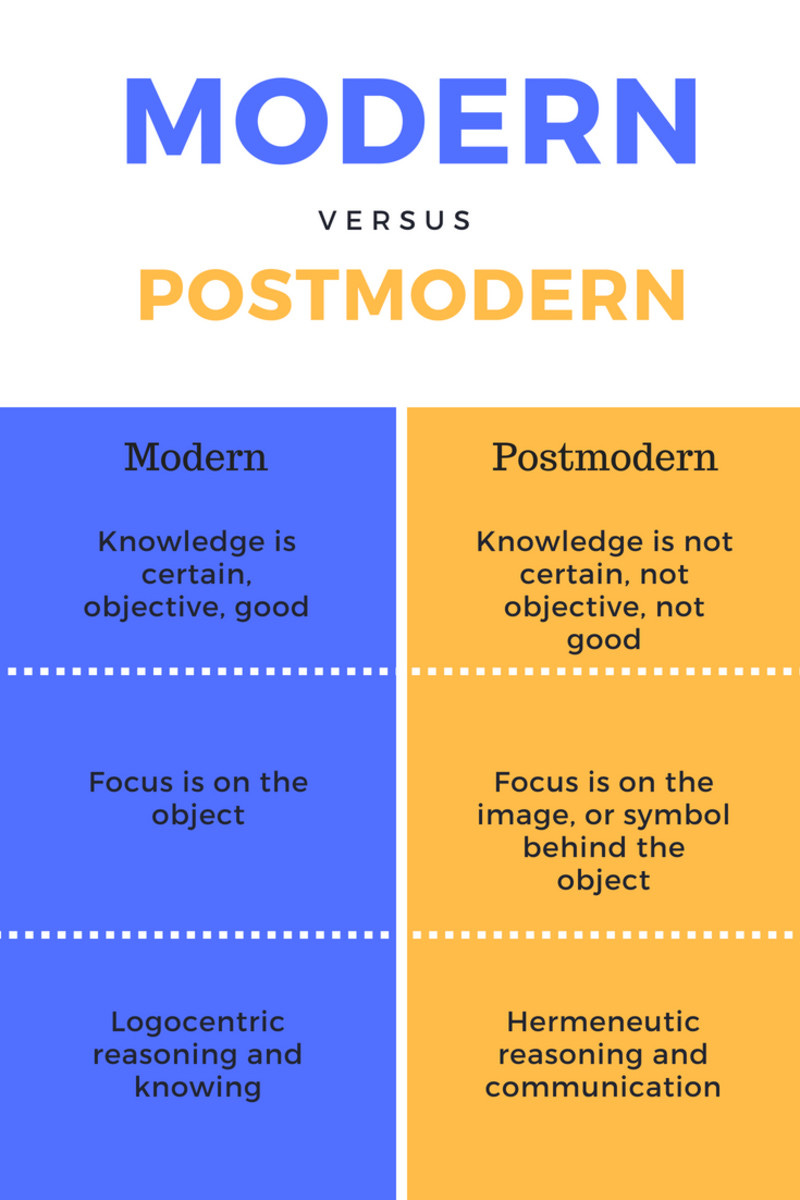

You have probably heard it said that postmodernism denies objective truth, that it questions the idea of any universal structure of thought, that it prioritizes the perspective of individuals rather than any big-picture (meta)narrative. And its not hard to see how Kant’s distinction might drive us to embracing uncertainty like this: after all, if the noumenal reality of the world is fundamentally unknowable to me, then isn’t all my thinking just that, my thinking, my subjective experience, shorn of any sure connection to reality?

This is the anxious question at the heart of postmodern thought, from Feuerbach through Nietzsche, Husserl, Heidegger, Peirce, Rorty, Levinas, Sartre, Baudrillard, Deleuze, Foucault, and beyond: if our knowledge cannot be secured to reality, then what are even doing when we write philosophy?

In Part 2, I will argue that there have generally been two basic ways that question is answered. One, I think, panics under the weight of Kant’s distinction, and produces what I (personally) think is bad postmodern thought. The other, though, takes Kant’s challenge with both greater courage but also more humility, and has given us profoundly important realizations: what I would consider good postmodernism. Please join me next week, when I will explicate the distinction between them, and argue for why (good) postmodernism is well worth your time.

Even though I used an image at the top of this article that, the internet tells me, is an example of postmodern visual art. Gotta have something catchy to lure in the readers! The ol’ painting-to-philosophy bait-&-switch. Pretty sure Plato did the same thing in the Agora.

Historians of philosophy, of course, may very well debate this. After all, Locke was writing at a similar time, and folks like Francisco Suárez had already raised significant critiques earlier in the century. Of course, things like modernism and the European Enlightenment can’t really be said to have one starting point on a particular day. Even so, I think identifying the start with Descartes’ Meditations is as good a point as any, if we are trying to get a big-picture hold on the matters at hand.

Though of course plenty of people did and do disagree with Kant here. I won’t be addressing those critiques here for a variety of reasons, but mostly because I am interested here in discussing that postmodernism developed from this insight, and not (yet) whether it should have.

It is important to reiterate this point, because many of Kant’s critics, past and present, seem to forget this and accuse Kant of being exactly the kind of “bad” postmodernist that I will describe in Part 2.

Or even pre-modernist philosophy, depending on which person was doing the contra-Kantian thing in question.

Though of course it did, and still does, have its proponents. I actually think there is plenty to appreciate in Hegel’s approach, and hope to write on him in the future. But I do think that on the phenomenal/noumenal distinction, he lost the battle with Kant.

The relationship between this development and the rise of materialism is very interesting, but not something I am going to pursue either here or in Part 2. I may return to it a later time—but, as mentioned in a previous piece, I’m trying to keep these things focused!

I tend to view early modernity—represented by thinkers like Descartes, Hume, Spinoza, and Leibniz—as grappling with the problem of grounding knowledge in the mind of the subject for the first time. This shift led to an effort to rewrite fundamental metaphysics in a way that could supersede classical metaphysics. With Descartes, for example, we see a rejection of formal and final causes and an explicit attempt to ground the existence of God and the certainty of knowledge within the subject. His famous dictum, Cogito ergo sum ("I think, therefore I am"), directly contrasts with the earlier tradition of thinkers like Aquinas, who might say, "I am, therefore I think."

The defining feature of modernity is that the grounding of reality no longer rests in God but in the mind of man. More importantly, modernity seems to be the first philosophical movement that attempts to construct metaphysics not as a continuation or development of tradition but in opposition to it. This "writing against" history often comes with an enormous investment in the power of a single individual to overturn and rewrite what took centuries of collective thought to develop.

This hubris—the belief that one person can accomplish what tradition achieved over generations—ultimately led to disillusionment. The supposed progress of modernity was starkly undermined by the horrors of the 20th century, leading to yet another revolt against the past. A revolt against a revolt: e.g. post-modernism.

Wait a minute, I thought postmodernism came from the "postmodern condition" essay! And isn't postmodernism an incredulity towards metanarratives, not an incredulity towards phenomena?